Gouraud: “Saladin, We’re Back!” Did The French General Really Say It on Conquering Syria in 1920?

James Barr | Originally published in Syria Comment

“Saladin, We’re Back!” So France’s general Henri Gouraud is said to have declared when he entered the Kurdish warrior’s tomb beside the Umayyad Mosque in August 1920 after the French had seized Damascus.

The quote seems plausible enough. Gouraud, in the words of his lieutenant, Georges Catroux, viewed his mission “as a Christian, as a soldier and a romantic”. He saw Damascus as the “unconquered fortress which defied the assaults of the Franks, the capital and burial place of the great Saladin, chivalrous victor over Lusignan at Hattin.It is one of those quotes that is too good not to use. Saladin’s biographer, Anne-Marie Eddé, starts her book with it to prove the endurance of her subject’s reputation, seven hundred years after his death. I quoted it myself in my 2011 history of the mandate era, A Line In The Sand. But when I was revising the text for the forthcoming French edition, I thought I might just check its source.

The quote seems plausible enough. Gouraud, in the words of his lieutenant, Georges Catroux, viewed his mission “as a Christian, as a soldier and a romantic”. He saw Damascus as the “unconquered fortress which defied the assaults of the Franks, the capital and burial place of the great Saladin, chivalrous victor over Lusignan at Hattin.”

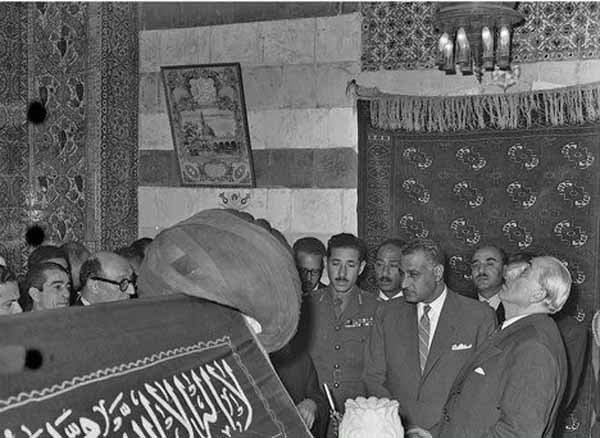

But did he actually tell Saladin he was back? The earliest evidence Eddé could find was in Gabriel Puaux’s Deux Années au Levant, which was only published in 1952, though Puaux served as France’s high-commissioner in the Levant from 1938-40. In this memoir Puaux says that Gouraud entered the tomb and exclaimed, “Saladin, nous voilà.” Despite Puaux’s distance from the events he was describing, this reference remains valuable because it predates the moment when the phrase gained more general notoriety when it was used by Nasser in a speech in March 1958 after he had visited Syria and seen Saladin’s tomb the previous month. Evidently it was a story frequently repeated in Damascus.

President Quwatli gives Nasser a tour of Salahidin’s tomb during his first visit to Damascus in 1958, when he came to sign the Syrian-Egyptian Union. The tomb of Saladin is located behind the Grand Umayyad Mosque in Old Damascus

But one man who had served in Gouraud’s army in 1920 did not certainly attribute it to Gouraud. In 1970, Louis Garros, by then a distinguished historian, wrote an article for Le Monde to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the French takeover of Syria. In it he referred only to “a general” entering the Umayyad mosque and saying “Saladin, nous voici”. It is unclear whether he was referring to Gouraud or his general Mariano Goybet, the man who actually took over Damascus.

Goybet entered Damascus on 25 July 1920. Gouraud made his formal entrance on 7 August. A reporter, Maria Rosette Shapira, who was attached to the French force, covered both events for the French weekly, L’Illustration. Shapira, who wrote under the pseudonym Myriam Harry, described the battle of Maysaloun and, briefly, Goybet’s arrival in Damascus in an article published on 21 August. It is her follow-up piece, which was printed on 11 September, that is of interest, because it hints that Goybet may have said something that caused offence.

Harry goes on to say that Gouraud preferred to sit outside in the shade of a lemon tree, from where they remarked on an ugly clock given by the Kaiser during his 1898 visit, which was fixed to the outside of the tomb. (Lawrence had of course made off two years earlier with the bronze wreath also given by the Kaiser, which is now in London’s Imperial War Museum). From there, Gouraud returned to the mosque where he was received by various Muslim dignitaries from the city. According to Harry Gouraud’s tone with these men was conciliatory. She reports him assuring them of his religious impartiality and his desire to maintain Arab independence. He then left to visit the Maidan.

Why the need for the emphatic denial that they did not enter the tomb? Given this was Gouraud’s first ever visit to Damascus, the implication of the sentence is that Harry had visited the tomb with Goybet and that whatever happened on that earlier occasion was controversial enough that it obliged Gouraud to make a show of not doing so himself on this first visit. The absence of any reference to Goybet’s visit to the tomb in Harry’s first piece, but then the reference to it in the second, makes me wonder whether the censor had been at work.

Unless a definitive eye-witness emerges, Harry’s reportage suggests that it was Goybet, rather than Gouraud, who is more likely to have made the notorious remark.

James Barr is an Historian. Author of A Line in the Sand, on how Anglo-French rivalry helped shape the modern Middle East.

Follow us on Twitter @DimashJournal