Remembering the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus

Louis Allday | Originally published in CounterPunch

The memories that I have of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, especially the atmosphere in its courtyard, are ones that I shall always cherish. The tragic events of the past four years have only served to make them more poignant.

The mosque is located a twenty minute walk away from the neighbourhood of Souk Sarouja, the area where I lived for much of 2009. During that time I visited it quite frequently. Occasionally, I would stop on the way and buy a traditional local ice cream, served with crushed pistachios on top, from the famous Bakdash ice cream parlour in the Hamadiyeh Souk (a popular market named after the Ottoman Sultan, Abdul Hamid II). I would usually finish the delicious, stretchy ice cream just as I approached the end of the covered souk, as the huge mosque becomes visible behind what remains of one of its predecessors, an ancient Roman temple dedicated to Jupiter.

Once inside the mosque’s courtyard, I would typically sit in the shade facing the exterior of the main prayer hall and watch the world go by. On one occasion, I fell asleep and had a completely blissful doze for what felt like an eternity, but in reality was only around half an hour.

The ambience in the courtyard is one that is difficult to describe to someone who has not experienced it themselves; bustling and full of life, but never hectic, spiritual without being solemn or intimidating and – above all else – enormously relaxed and friendly. Daily, the courtyard would host a thronging mix of families sitting in groups quietly eating and laughing together; local worshippers popping in quickly to pray; foreign pilgrims exploring the mosque’s numerous sites of religious significance and tourists holding guide books and cameras, all of this set against the soundtrack of children’s laughter and the soft noise of shoeless feet shuffling over ancient marble polished so bright that it shone as if it were wet.

The Umayyad Mosque is one of the oldest and largest in the world and is generally considered to be the fourth most important religious site in Sunni Islam. It is also an extremely important site to Shia Muslims, as it is the location of a shrine believed by some to contain the head of the Imam Hussein, grandson of the Prophet Muhammad (others believe Hussein’s head was moved to al-Hussein Mosque in Cairo by the Fatimids). It is the location where the Umayyad Caliph, Yezid is said to have brought the women and children of Imam Hussein and his followers after the Battle of Kerbala in 680, during which Hussein was killed (and beheaded). As such, the mosque is a popular pilgrimage site for Shia Syrians, as well as Shia from other countries including Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan and Afghanistan. I would often see streams of Shia pilgrims walking across the courtyard to the shrine where Hussein’s head is said to be located.

In April 2009, I entered this shrine for the first time a little apprehensively and to my amazement discovered that there was no one else around. As I stood alone in the room, I felt a powerful connection to the past as I touched the shrine’s surprisingly cold metal lattice. Whether or not it actually contained Hussein’s head or not seemed unimportant. Not long after I arrived, a large group of Iraqi pilgrims, mainly elderly and middle-aged women, entered the room en masse and began to chant in unison around me “oh Hussein, oh Hussein”. Many began to sob uncontrollably and I had the distinct feeling that it was not just for the martyrs of Kerbala that they were crying, but for their own personal losses and disappointments. One particularly elderly woman smiled sweetly and apologised when she trod on my foot. The atmosphere of mourning and lamentation began to feel overwhelming and a strong feeling of sadness started to swell in my chest as tears formed in my eyes. Beginning to feel like a voyeur, peering at the grief of others, I left the room not long after the pilgrims had entered.

Initially a Roman temple dedicated to Jupiter, the site where the mosque now lies was later transformed into a Christian cathedral that, in around the sixth century, came to be dedicated to John the Baptist (or Yahya in Arabic). His head is believed to be buried on the site, and a shrine said to contain it remains an integral part of the mosque to this day. The shrine is located prominently in the mosque’s main prayer hall and is regularly visited by both Muslims and Christians alike.

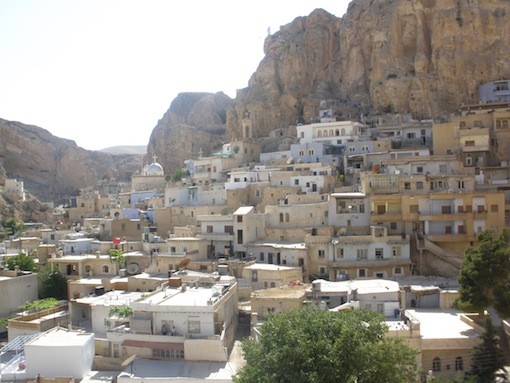

This kind of inter-religious mingling can be surprising to some in the West, but it was something that I saw time and again during my stay in Syria and was clearly an intrinsic part of daily life in the country. I witnessed another striking example at the Greek Orthodox monastery of Saint Thecla in the town of Ma’loula, located in the mountains north-east of Damascus. The majority of the town’s population are Christian and it is one of the few remaining places on earth where a form of Aramaic, ‘the language of Jesus Christ’ is still spoken. Here, local Syrians – both Christian and Muslim alike – as well as foreign tourists like me used to visit the monastery, where it is believed a mountain miraculously cracked in two, allowing Saint Thecla to flee the her family’s wrath after her conversion from paganism to Christianity. Visitors drink holy water that seeps from the crack in the cliff as it is claimed to have miraculous healing qualities. The motto of the town’s residents is said to have been “Everyone is a Christian and everyone is Muslim”.

Tragically, in September 2013, the town was attacked by Jabhat al-Nusra, a terrorist group and al-Qaeda affiliate widely claimed to have been funded by Qatar and Saudi Arabia and that has fought alongside fighters armed and trained by the US. The group’s attack on Ma’loula – which was begun by a Jordanian suicide attacker – caused devastating damage and many of the town’s churches and monasteries were targeted. Two months later, a coalition of armed groups including Jabhat al-Nusra attacked Ma’loula again and kidnapped twelve nuns from the Saint Thecla monastery (thankfully the nuns were subsequently released unharmed in a negotiated exchange in March 2014). During the fighting, the monastery itself was burnt and its holy icons and relics looted and vandalised. In April 2014, the town was re-captured by the armed forces of the Syrian Government , and as of November 2015, it remains under government control. However, many of its traumatised residents are yet to return home, and although much of the physical devastation that the town suffered will hopefully be repaired, restoring the spirit of co-existence and tolerance that previously characterised the town and relations between its Christian and Muslim inhabitants will be significantly harder to re-build, if it can be at all. It is exactly this type of plurality and religious diversity – highly precarious and imperfect though it undoubtedly was – that the West and its allies have done so much to destroy, specifically in Syria, but also across the region as a whole. As is so often the case, the West has facilitated the destruction of a society that expressed many of the very values it claims to defend.

I am conscious that my experience in Syria was ultimately one of a privileged outsider; I was only ever a temporary resident and the reality is that, even then, many of my Syrian friends expressed a strong desire to leave the country. Given the devastation witnessed over the past four years it is easy to be nostalgic about Syria’s recent past; as famously observed by Marcel Proust, “remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were”.

It is not my intention to imply that Syria before 2011 was some kind of paradise, far from it. However, I remain convinced that anyone who spent any length of time in Syria before its civil war began, would tell you that there was something extremely special about the diversity, tolerance and kindness one witnessed so frequently in Syrian society. Many of those who wanted to leave were subsequently forced to do so and are now refugees. Most of them feel a deep longing to return to the country they previously wanted to escape.

In September 2009, a close friend of mine with no prior knowledge of Syria or the Middle East visited me for a week and we travelled all over Syria together, including trips to Ma’loula, Aleppo, Homs, Bosra and Palmyra as well as the Umayyad Mosque. One of his overwhelming impressions from the time that he spent in the country was how incredibly friendly and polite Syrians were to one another. I sincerely hope that this gentleness, compassion and tolerance has not been entirely lost in the ravages of war. Despite the suffering of the past four years, I hope that Syria is somehow able to rebuild itself and remain a pluralistic, diverse society, not one dismembered into crude ethno-religious statelets, as so many of its enemies clearly desire.

Louis Allday is a PhD candidate at SOAS based in London.

Follow us on Twitter @DimashqJournal